When I think of a city hall, I think of Gotham City that resides in Batman’s fictional land of injustice. In Australia these places are a rarity and my hometown of Brisbane contains the country’s only city hall to reside in a capital city. A city hall, I discovered, differs from a town hall in that its civic duties are carried out inside its walls. Additionally, Brisbane City Hall is home to some interesting history and a shred (or two) of mystery.

The clock tower

Starting at the top, I discovered when Brisbane City Hall was opened to the public in 1930, its 92 metre clock tower was Australia’s tallest and most modern time-keeping piece, right up until the 1960s. In fact, it was once fitted with a scarlet beacon to warn aircraft of its presence.

Fast forward to November 2018 and I found myself riding to the top on a free guided tour (which run daily) in Australia’s oldest manually operated lift. The lift’s interior and my elderly companions made me feel as if I was ascending to a rooftop session of ‘60s bingo. While I enjoyed the lofty views over Brisbane city, I couldn’t really see the timepiece up close (as I’d hoped).

There’s also five bells in the clock tower, four of which are called the Cambridge Chimes, while the fifth is a larger hour bell that weighs over four tonnes. Unfortunately I only got a hazy view of these through a dirty glass ceiling. In all, it’s worth the 15 minute tour, especially for the elevator ride, but don’t expect much more than a decent view.

Brisbane City Hall’s dark side

At the conclusion of Brisbane City Hall’s main tour – which I experienced later and which finishes at the base of the clock tower – I asked our guide Rachel whether she knew of the rooms collectively known as ‘room 302’. Surprisingly, despite her seemingly endless knowledge of city hall, Rachel told me she’d never heard of them.

When I first encountered Brisbane City Hall on a ghost tour back in 2014, our group was told there were four ghosts residing in room 302 at city hall. Apparently two people committed suicide from the clock tower, although further research hasn’t confirmed this.

The ABC, however, reported “at least three ghosts” are believed to roam city hall and the Queensland Government reports one suicide at city hall and mentions one resident ghost. Both have reported the existence of the rooms known as room 302, although I was disappointed to discover they had been removed in the ‘80s, apparently as the result of “sinister” activity.

The war

During WWII, Brisbane City Hall was the focus of Brisbane activity and American soldiers livened the scene with jazz music. Allegedly the hall hosted Brisbane’s best jazz scene at the time, along with rallies, marches, fund raisers and various concerts.

In 1945, a soldier wrote his name on the toilet wall downstairs and 150 others followed suit. Some soldiers wrote where they came from and a lady allegedly tracked them down and discovered they had all returned from WWII. A book called The Soldiers’ Wall: A Glimpse Into Their World (available in the city hall’s museum) reveals the story.

Brisbane City Hall – rags to riches

In the 1900s, the site of Brisbane City Hall was a swamp known as “the horse pond”. Indeed, when construction commenced in 1920 there was very little fresh water available for concrete. The construction therefore developed ‘concrete cancer’, which endured until the $215 million upgrade it received (and so desperately needed) in 2010.

It’s a good thing it’s now in superb shape, as the staircase inside the foyer is made from Italian Carrara marble (considered the finest in the world), allegedly from the same quarry as Michelangelo’s Sculpture of David. Other stylish additions include the ceiling plasterwork and foyer chandelier done in the art-deco style of the ‘20s and ’30s.

It would be remiss of me if I didn’t mention Brisbane City Hall’s whopper copper dome, the largest of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere at 31 metres across and weighing 20 tonnes. In 2003 the original dome had to be replaced as kids throwing coins onto it over the years caused substantial structural damage.

The ceiling beneath the dome supports over 8500 LED lights and a central light known as the oculus. This forms the roof of the auditorium, a structure based on the design of Rome’s Pantheon. Our group nearly missed a viewing, but I made sure I stuck my face and camera inside to get a glimpse of the auditorium, which was (at least on this day) a vast luminous sanctuary, complete with an orchestra.

The origins of Brisbane

Brisbane was named after a Scottish army officer and astronomer named Sir Thomas Brisbane. During his lifetime Sir Thomas catalogued over 3,700 stars, which are on record inside the city hall. Also of interest is ‘Largs door’ from Sir Thomas Brisbane’s home in Largs, Scotland, which was destroyed by a fire in 1939. The door now resides in Brisbane City Hall.

The Shingle Inn

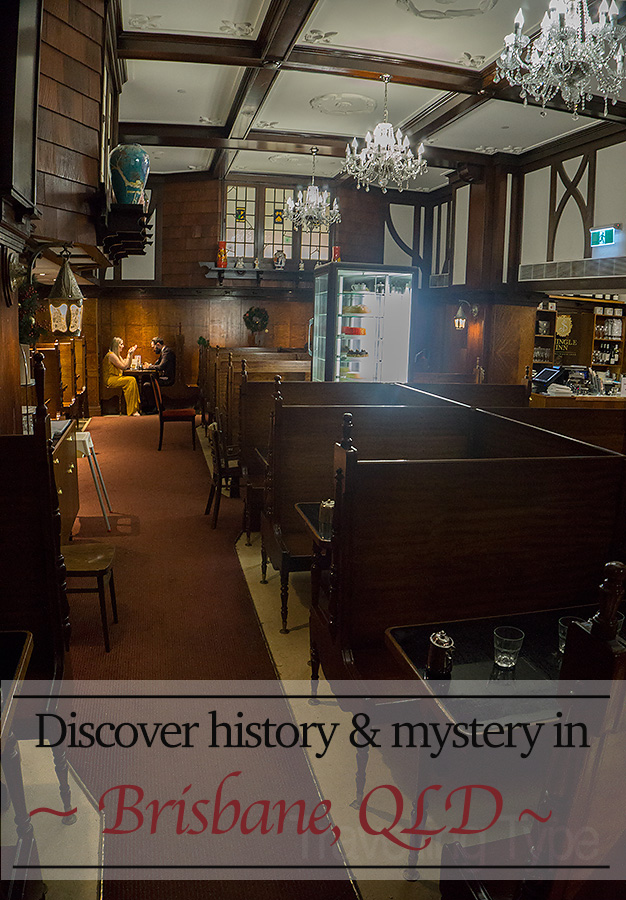

Lastly, a place where I occasionally hide away and write is inside the iconic Shingle Inn, which now lives on the ground floor of Brisbane City Hall.

Built on Brisbane’s Edward Street in 1936, the Shingle Inn began as an “elegant English tea-style house and restaurant” before becoming a chain café/restaurant. Today there’s 19 Shingle Inns in the Brisbane area, two in the Sunshine Coast, two in the Gold Coast, one in Toowoomba, one in the Central Coast and one in Sydney. However it was the original Shingle Inn that faced dereliction in 2002 before it was saved and moved to its current location in Brisbane City Hall, complete with original interior.

Inside it’s small but cosy and it feels distinctly European sitting in its spartan booths, beneath shingle cladding and leadlight windows while sipping tea.

In all, Brisbane City Hall is well worth a visit, especially as it’s free to investigate. It’s also highly likely you’ll discover something new.

Maybe even a secret…